Milton Keynes: a vision of Anglofuturism

Demolish Milton Keynes and replace it with the city of the future.

Owing to my tragically paltry social life, I find myself spending embarrassingly large amounts of time browsing on Google Earth. One of the great wonders of modern technology, it allows me to explore the most distant and obscure parts of our planet in fine detail, from American metropolises to remote Nepalese villages. Yet I have found myself fascinated with one corner of the Earth rather closer to home: Milton Keynes.

Built from the late 1960s, Milton Keynes was the most ambitious of the post-War new towns that sprang up across the country to relieve inner-city housing congestion. Intended to house 250,000 residents, planners were keen to avoid the mistakes that had plagued previous new towns. Gone were the looming concrete tower blocks — Milton Keynes was to be a low-rise city of trees dispersed between striking modernist architecture. Unlike the radial and organic design of most British towns, Milton Keynes was designed on a rough grid pattern, with major fast roads known as ‘grid roads’ spaced roughly a kilometre apart enclosing various neighbourhoods. These grid roads form the town’s arteries, and provide fast access between each grid and the town’s centre.

Despite (or maybe because of) a star-studded line up of architects working on the town, the unique experiment that was Milton Keynes quickly became a symbol of mockery and scorn. Derided as sterile, paternalistic, uncomfortably American and above all weird, the high-minded idealism of the planners materialised as suburban mundanity. A few eccentric admirers notwithstanding, for most Brits Milton Keynes joins the likes of Stevenage and Crawley as a cautionary example of the folly of giving the government the responsibility to design and build whole new towns from scratch. Today, the town built for the future is already looking out of date.

But despite its derisory reputation, Milton Keynes has been quietly and unglamorously economically successful. In 2019, Milton Keynes had a GDP per head of £58k, well ahead of the UK average of £33k. The town has some of the highest productivity in the country, has become a start-up hub, and has leveraged its proximity to Silverstone Circuit to become a centre for the country’s high-end engineering sector. Its modular design has allowed for continued growth in the town’s housing stock, keeping average house prices below most other major urban areas in the region. It also benefits from its location at the intersection of the country’s two largest cities, London and Birmingham, and two most important university towns, Oxford and Cambridge, with direct rail connections to London and Birmingham taking just 32 and 56 minutes respectively. When construction of the East West Rail (eventually) completes, Milton Keynes will become a central node on the Oxford to Cambridge railway line and will fall within commuting distance of both.

Given these sound foundations, I think Milton Keynes could once again be the key to alleviating Britain’s housing shortage. Labour recently announced that they will turn to the likes of Milton Keynes as inspiration for a new generation of towns which will help fulfil their 300,000 per year housing target, and speculation immediately ensued over which parts of this green and pleasant land will make way for roundabouts and shopping centres. But I would wager that there is no need to turn more fields into Barratt Boxes — we should instead (literally) build on the attempts of previous generations to alleviate their housing shortages to deal with our own. The plan should not be to build more Milton Keyneses, but to rebuild and transform the one that already exists.

The ambition should be for a redeveloped Milton Keynes (MK2) to leverage its extant competitive advantages to become a major British centre of growth, sucking up all the new companies that are currently unable to grow in the likes of Oxford and Cambridge owing to a lack of lab/office space and affordable housing for employees. The current town’s design offers an excellent base upon which to build; the grid roads were designed with plenty of space beside them to allow for easy expansion or the addition of future transit lines. MK2 would thus be able to cheaply build a number of light rail lines, to be modelled off of Brescia’s autonomous metro, connecting its various neighbourhoods to the centre and rail station cheaply, quickly, and efficiently.

With construction having started more than half a century ago, much of Milton Keynes’s building stock is approaching the stage in its lifecycle where significant and costly repair work is needed to keep it viable — and it shows. This presents an opportunity: instead of sinking more money into ugly and inefficient buildings, now is the time to demolish them and replace them with something altogether better. My proposal would be to rekindle the spirit of ambition that Milton Keynes was founded on and set out a masterplan to completely transform the town.

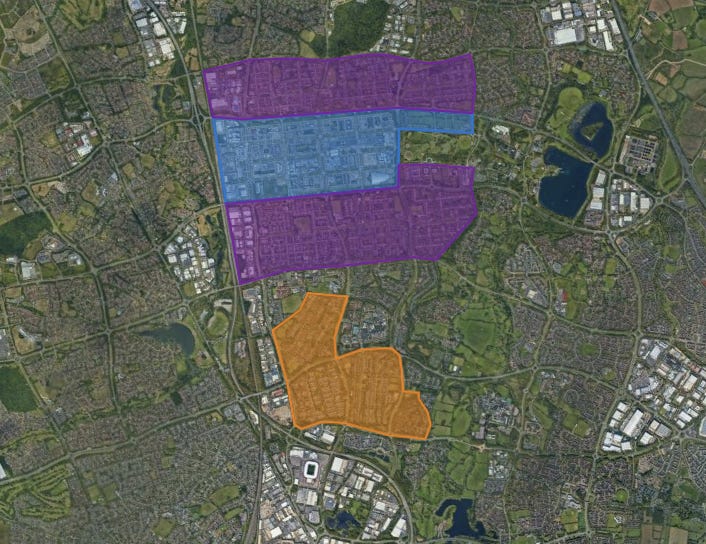

The centre of MK2, currently mostly surface level car parking, dreary office blocks, and a few new midrise developments, would be completely cleared to make way for a dense urban core comprised of 10-20 story mixed use buildings, with an urban landscape inspired by that of Manhattan. Milton Keynes already contains wide, tree-lined boulevards that are well suited to high density buildings buttressed either side. The dense core would be the heart of the city, with the tall buildings offering perfect homes to start-ups and growing businesses in need of cheap, high quality office space. It would also provide a cultural heart to MK2, housing a variety of pubs, bars, clubs and so on, all unrestricted by the draconian licensing laws that have a stranglehold over London. Like with the redeveloped city as a whole, a style guide would be given to developers dictating the heights, materials and proportions of the buildings (no ugly plastic cladding), but other cumbersome impositions like affordable housing targets or bee bricks would be scrapped. The spirit of MK2’s centre will flip from one of office park dullness to one of youth, vitality, verve and opportunity. It will be busy and exciting, the place to go for those with big ideas and even bigger ambitions, the place that will birth the next AstraZenecas and Gymsharks, the place for British graduates to flock to in search of good salaries and affordable housing. It will be where future Anglo prosperity will be made.

The dense core of MK2 will then be surrounded by medium-density, mostly residential development. Modelled off of the best examples of Belle Époque urbanism, it will emulate the likes of South Kensington and offer cheap but somewhat constrained city living in tastefully designed mansion blocks. Perfect for those at the start of their career who want to live in a vibrant neighbourhood full of amenities, without being engulfed by the hubbub of the city centre, these areas will provide housing for up to 100,000 of MK2’s residents1.

Finally, the third type of development would take inspiration from the best of Anglo urbanism, replicating the genteel suburbs of the Georgian and Victorian era that can be found across the country, in places such as Edinburgh, Brighton and Islington. Here, the Englishman will be able to have his castle in the form of a multistorey townhouse or semi, with multiple bedrooms and spacious back gardens. Within a short light rail commute of the centre, they offer the opportunity to put down roots and start a family in a beautiful, tranquil neighbourhood.

MK2 would go a long way to relieving the South East’s pressing housing shortage, but its impact would go much further than that. MK2 will show that stagnation and melancholy nostalgia for previous epochs of growth and self-confident optimism is not the only option — Britain’s best days still lie ahead, and a future that is better than the present is possible. MK2 will show how Britain can adapt to looming challenges, by supporting and growing resilient economic sectors rather than yearning to return to those that have long ceased to be profitable, by using the technologies of the future, from nuclear energy to autonomous delivery robots, thereby preparing for a world of net-zero and sub-replacement fertility, and by doubling HMP Woodside to lock up repeat offenders and usher Singapore levels of public safety.

My proposal for MK2 is unboundedly ambitious, but no less ambitious than the original plan for the town or than Labour’s plans to build other new towns from scratch. Tens of thousands of current residents would have to be displaced and there would be unanimous local opposition, but all growth comes at a cost and sweeteners could be made. The history of Britain’s growth and industrialisation has been one of displacements and change — there is no eternal principle dictating that all things must be kept exactly as they are in the present and that no building or area may ever be replaced. If there were, we would all still be living in mud huts and mostly dying a few months after birth. As big as the political and social cost of completely redeveloping Milton Keynes is, the opportunity cost of not doing so is arguably greater.

The philosophy guiding the creation of Milton Keynes was one of experimentation and novelty, seeking to create a place like no other that would propel Britain into the future. Milton Keynes was never meant to be static and staid; from its inception it was to be the town where the future happened. Circumstances have changed in the 50 years since its creation, and our vision of the future is no longer one of infinite roundabouts and suburban retail parks. It should be one of cutting-edge technology, urban vibrancy, traditional Anglo beauty, national interconnectivity, and material abundance. Not minimalist low-rise apartments and concrete bungalows, but ornate mansion blocks and neo-Georgian townhouses. Not a city centre of parking lots and dreariness, but a Manhattan of Europe and spirit of ambition. Not country of gerontocracy and NIMBYism, but vitality and Anglofuturism.

The two purple zones come to a combined area of just over 5 km2, which at a Parisian density of around 20,000/ km2 means over 100,000 people could be housed in that area alone.

I wish you would post more often as you’re an original and exciting writer. This piece ranks as one of my favourite on Substack.

This is brilliant. Please go and work for the government. This one if you must, or the next one which might be more open to this sort of thing.